Cell states in the cell_a_v platform are composed of several parts. Every state has assigned an alphabetic 'character'. States can also have an associated 'link', which consists of one or more 'vectors' that point to another square, either in the same or another world.

The 'character' part of the state is defined for every square in the CA lattice at each time.

The characters are from the range a-z and A-Z.

To increase the number of possible characters an optional apostrophe is supported,

allowing states like a' and Z' (pronounced a-prime or a-dashed),

sometimes called alternate states. Note that the primed characters are still considered and handled as a single character.

The four ranges a-z, A-Z, a'-z' and A'-Z' then allow up to 104 distinct state characters.

For the purpose of effective visualization, each character state is also assigned a color.

This is completely arbitrary and ignored by the engine (the state could be displayed using just an alphabetic character instead).

As a convention, states from the uppercase range have the same color as their lowercase counterparts, but lighter.

Alternate states have a horizontal stripe of the opposite color across the square.

Any subset of the allowed 104 characters can be defined as 'link states' or 'vector states'. This is specified in the meta-data part of the rules file and may be different from project to project.

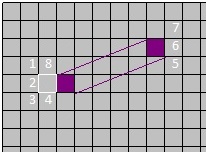

Vector states have an associated 'link', which consists of one or more 'vectors' that point to another square.

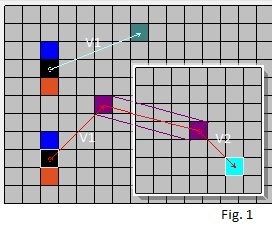

When the link points to a square in the same world, only one vector is needed that specifies the location of the other square (it may point to itself).

A link cannot point to a square in another world directly. However, it may do that by going through a wormhole.

To do this, two vectors are required: the first points to the location of the wormhole and the second points from the other end of the wormhole

in the other (or possibly the same) world to the target square.

Fig. 1 shows an example of both cases.

While it would be possible for the link to go through multiple wormholes, by utilizing more than two vectors,

that is not supported by the platform at this time.

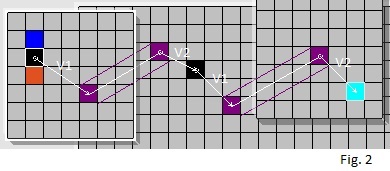

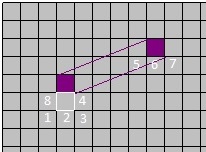

The same effect is achieved by alternating the wormholes with mirror-states (see Fig. 2):

the base square points via a wormhole to a mirror state in another world and that in turn

points via a wormhole to yet another world and so on.

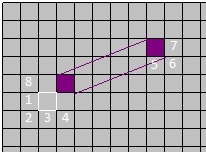

Links also have an attribute indicating one of two types: relative and fixed.

It is important to note that there is no difference between them as far as the effect on the neighborhood.

The engine follows both of these link types exactly the same.

The difference is in how they are considered when used to assign or update a link of another square.

relative links

When a link is updated or assigned to some cell based on a relative link (like a link of the last matched square),

the same vector is placed at the result square (the rule's base square).

For example, if the matched square link vector pointed 'one square up and three to the right',

the assigned link vector will also point 'one square up and three to the right'.

This also means that, since the matched and updated squares are different, the squares they will point to will be different as well.

fixed links

When a link is updated or assigned to some cell based on a fixed link, the resulting vector will point to the same square as the original, so it will need to have different (x, y) values.

The relative and fixed links are displayed using a slightly different color.

The platform supports the concept of state sets. States that are part of each set are defined per project in the metadata, each set is a subset of the allowed 104 character states. They fall into one of two categories:

numbered state sets, referred to in rules as #n, where n is a number from 1 - 9. They can be used to greatly reduce the number of rules required, by making a generic reference to the whole set instead of each state separately.

built-in state sets. These allow designating states that receive 'special handling' by the engine. They include link states, mirror states, inverting states and wormholes.

Link States or Vector States are states that have an associated 'link', which points to another square as described above.

When the engine encounters a mirror state in a cell neighborhood it automatically (by default) follows its link and uses the state of the square it points to. For the details of this process see the Rules page.

In most examples on this website, the states o and o' are defined as mirror states.

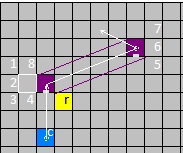

Inverting States are link states that change set membership of the state the link points to to its opposite.

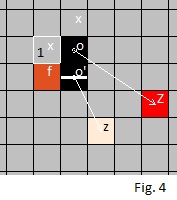

For example, assume the state o' is defined as an inverting state (o is not)

and the state Z is a member of state set #3,

while the state z is not a member of state set #3.

When the state o' pointing to z is encountered in some cell's neighborhood,

it will match the rule test string #3.

The state o (non-inverting) would need to point to Z

rather than z to match the rule test string #3.

For example in Fig. 4, the base square 1 will match the rule xf#3#3x=Z

In most examples on this website, the state o' is defined as an inverting state.

One or more states may be defined as wormhole states by including them either in the 'wormholes-open' or the 'wormholes-closed' built-in state-sets specified in the metadata.

In most examples on this website, the state w is defined as an open wormhole state and the state W is defined as a closed wormhole state.

The wormhole state is special in that it may connect two different worlds or two parts of the same world.

For the connection to be active, there must be two distinct wormhole states, also referred to as wormhole ends, both must be open and they must be double-linked (i.e. they must point to each other).

When the two wormhole ends are double-linked, but one or both are closed, the connection is inactive (the wormhole is closed): links cannot go through and the neighborhood is not affected. However, the connection persists in the sense that the ends still 'track' each other and the wormhole may be re-opened, when both ends are changed to open again.

To keep track of the square where the wormhole is pointing it needs an index of the other world (may be the same world) and a vector that points to a square in that world. When the wormhole is connected (the two ends are double-linked), the engine takes the two ends as being one cell (being in two worlds at the same time) in the sense that a change to one may affect the other. This allows the concept of a moving wormhole.

moving wormhole

When a square adjacent to a wormhole state is changed to a wormhole, it usually inherits the original's information

(controlled precisely by the specific rule). Very often the original wormhole changes to another state at that time.

If the original wormhole state was double-linked, the engine updates the other end to keep it connected

to the 'new location' of the end that has 'moved'.

Hover over Fig. 5 to see an animation of a moving wormhole.

There is also an example of a moving wormhole that avoids obstacles in the Gallery.

An open wormhole connects the two ends in two ways: links may point through it and its neighborhood is warped.

links pointing through a wormhole

Links from other cells may point to another world by first pointing to an open wormhole end and then from the other end to a target square.

See description and examples above.

wormhole neighborhood

Any square adjacent to an open wormhole has its neighborhood affected or 'warped'.

To understand the neighborhood around a wormhole, imagine bending the right half of the CA lattice back and

aligning it so that the two wormhole ends touch,

then punching a hole through the two squares (one is on top of the other) and gluing the resulting edges together.

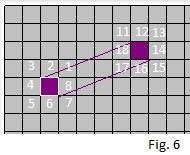

Mark the corresponding squares 1 - 8 on one side, 11 - 18 on the other.

However, to see the whole lattice again, you have to 'unfold' the back part of the sheet to front again and that involves a flip!

You can choose to flip it horizontally or vertically (this could be made configurable, but currently the platform always uses a horizontal flip).

The resulting mapping is shown in Fig. 6.

This explains why a 'glider' going through a wormhole from left to right will continue going left to right on the other side, however, a glider going down through a wormhole will emerge going up (see example in the gallery).

When a square is adjacent to an open wormhole end, its neighborhood has three squares replaced with states of squares from the other side. A few such cases are illustrated below:

wormhole rotation

Each wormhole end may be rotated. The resulting 'angle' is limited only to the four orthogonal directions, so the rotation is described by a modulo-4 number, with 0 for a wormhole state that is not rotated.

Wormhole state rotation may be changed by a rule.

For example the rule wr@+ will rotate the wormhole end 90 degrees clockwise when matched.

Rotation of a wormhole affects both the links going through it and the neighborhood of the adjacent cells.

The effect is illustrated by the following image sequence -

presence of the state r rotates the wormhole clockwise by 90 degrees in each subsequent frame.

Note that the link of square c remains the same in all frames: V1=(0,-3), V2=(-2,-1).

The 5th frame will be identical to the 1st one (rot 0).

For an example with a rotating wormhole see the Gallery.

Use of the state sets is not required, the same functionality can be achieved without them. However, the number of rules needed would be much larger and they would be much less elegant.